Command-line Accounting in Context

Martin Blais, July 2014

http://furius.ca/beancount/doc/motivation

This text provides context and motivation for the usage of double-entry

command-line accounting systems to manage personal finances.

Why not just use a spreadsheet?

Why not just use a commercial app?

Why build a computer language?

Advantages of Command-Line Bookkeeping

Motivation

When I tell people about my command-line accounting hacking activities, I get a variety of reactions.

Sometimes I hear echoes of desperation about their own finances: many people wish they had a better handle and understanding of their finances, they sigh and wish they were better organized. Other times, after I describe my process I get incredulous reactions: “Why do you even bother?” Those are the people who feel that their financial life is so simple that it can be summarized in 5 minutes. These are most often blissfully unaware how many accounts they have and have only an imprecise idea of where they stand. They have at least 20 accounts to their name; it’s only when we go through the details that they realize that their financial ecosystem is more complex than they thought. Finally, there are those who get really excited about the idea of using a powerful accounting system but who don’t actually understand what it is that I’m talking about. They might think it is a system to support investment portfolios, or something that I use to curate a budget like a stickler. Usually they end up thinking it is too complicated to actually get started with.

This document attempts to explain what command-line bookkeeping is about in concrete terms, what you will get out of doing it, how the various software pieces fit together, and what kinds of results you can expect from this method. The fact is, the double-entry method is a basic technique that everyone should have been taught in high school. And using it for yourself is a simple and powerful process you can use to drive your entire financial life.

What exactly is “Accounting”?

When one talks about “accounting,” they often implicitly refer to one or more of various distinct financial processes:

-

Bookkeeping. Recording past transactions in a single place, a “ledger,” also called “the books,” as in, “the books of this company.” Essentially, this means copying the amounts and category of financial transactions that occur in external account statements to a single system that includes all of the “accounts” relating to an entity and links them together. This is colloquially called “keeping books,” or the activity of “bookkeeping.”

-

Invoices. Preparing invoices and tracking payments. Contractors will often bring this up because it is a major concern of their activity: issuing requests to clients for payments for services rendered, and checking whether the corresponding payments have actually been received later on (and taking collection actions in case they haven’t). If you’re managing a company’s finances, processing payroll is another aspect of this which is heavy in bookkeeping.

-

Taxes. Finding or calculating taxable income, filling out tax forms and filing taxes to the various governmental authorities the entity is subject to. This process can be arduous, and for people who are beginning to see an increase in the complexity of their personal assets (many accounts of different types, new reporting requirements), it can be quite stressful. This is often the moment that they start thinking about organizing themselves.

-

Expenses. Analyzing expenses, basically answering the question: “Where is my money going?” A person with a small income and many credit cards may want to precisely track and calculate how much they’re spending every month. This just develops awareness. Even in the presence of abundant resources, it is interesting to look at how much one is spending regularly, and where most of one’s regular income is going, it often brings up surprises.

-

Budgeting. Forecasting future expenses, allocating limited amounts to spend in various categories, and tracking how close one’s actual spending is to those allocations. For individuals, this is usually in the context of trying to pay down debt or finding ways to save more. For companies, this occurs when planning for various projects.

-

Investing. Summarizing and computing investment returns and capital gains. Many of us now manage our own savings via discount brokers, investing via ETFs and individually selected mutual funds. It is useful to be able to view asset distribution and risk exposure, as well as compute capital gains.

-

Reporting. Public companies have regulatory requirements to provide transparency to their investors. As such, they usually report an annual income statement and a beginning and ending balance sheet. For an individual, those same reports are useful when applying for a personal loan or a mortgage at a bank, as they provide a window to someone’s financial health situation.

In this document, I will describe how command-line accounting can provide help and support for these activities.

What can it do for me?

You might legitimately ask: sure, but why bother? We can look at the uses of accounting in terms of the questions it can answer for you:

-

Where’s my money, Lebowski? If you don’t keep track of stuff, use cash a lot, have too many credit cards or if you are simply a disorganized and brilliant artist with his head in the clouds, you might wonder why there aren’t as many beans left at the end of the month as you would like. An income statement will answer this question.

-

I’d like to be like Warren Buffet. How much do I have to save every month? I personally don’t do a budget, but I know many people who do. If you set specific financial goals for a project or to save for later, the first thing you need to do is allocate a budget and set limits on your spending. Tracking your money is the first step towards doing that. You could even compute your returns in a way that can be compared against the market.

-

I have some cash to invest. Given my portfolio, where should I invest it? Being able to report on the totality of your holdings, you can determine your asset class and currency exposures. This can help you decide where to place new savings in order to match a target portfolio allocation.

-

How much am I worth? You have a 401k, an IRA and taxable accounts. A remaining student loan, or perhaps you’re sitting on real-estate with two mortgages. Whatever. What’s the total? It’s really nice to obtain a single number that tells you how far you are from your retirement goals. Beancount can easily compute your net worth (to the cent).

-

I still hurt from 2008. Are my investments safe? For example, I’m managing my own money with various discount brokers, and many people are. I’m basically running a miniature hedge fund using ETFs, where my goal is to be as diversified as possible between asset classes, sector exposure, currency exposure, etc. Plus, because of tax-deferred accounts I cannot do that in a single place. With Beancount you can generate a list of holdings and aggregate them by category.

-

Taxes suck. Well, enough said. Why do they suck? Mostly because of uncertainty and doubt. It’s not fun to not know what’s going on. If you had all the data at your fingertips instantly it wouldn’t be nearly as bad. What do you have to report? For some people there’s a single stream of income, but for many others, it gets complicated (you might even be in that situation and you don’t know it). Qualified vs. ordinary dividends, long-term vs. short-term capital gains, income from secondary sources, wash sales, etc. When it’s time to do my taxes, I bring up the year’s income statement, and I have a clear list of items to put in and deductions I can make.

-

I want to buy a home. How much can I gather for a down payment? If you needed a lot of cash all of a sudden, how much could you afford? Well, if you can produce a list of your holdings, you can aggregate them “by liquidity.” This gives you an idea of available cash in case of an urgent need.

-

Mr. Banker, please lend me some money. Impress the banker geek: just bring your balance sheet. Ideally the one generated fresh from that morning. You should have your complete balance sheet at any point in time.

-

Instructions for your eventual passing. Making a will involves listing your assets. Make your children’s lives easier should you pass by having a complete list of all the beans to be passed on or collected. The amounts are just part of the story: being able to list all the accounts and institutions will make it easier for someone to clear your assets.

-

I can’t remember if they paid me. If you send out invoices and have receivables, it’s nice to have a method to track who has paid and who just says they’ll pay.

I’m sure there is a lot more you can think of. Let me know.

Keeping Books

Alright, so here’s the part where I give you the insight of the method. The central and most basic activity that provides support for all the other ones is bookkeeping. A most important and fundamental realization is that this relatively simple act—that of copying all of the financial transactions into a single integrated system—allows you to produce reports that solve all of the other problems. You are building a corpus of data, a list of dated transaction objects that each represents movements of money between some of the accounts that you own. This data provides a full timeline of your financial activity.

All you have to do is enter each transaction while respecting a simple constraint, that of the double-entry method, which is this:

Each time an amount is posted to an account, it must have a corresponding inverse amount posted to some other account(s), and the sum of these amounts must be zero.

That’s it. This is the essence of the method, and an ensemble of transactions that respects this constraint acquires nice properties which are discussed in detail in some of my other documents. In order to generate sensible reports, all accounts are further labeled with one of four categories: Assets, Liabilities, Income and Expenses. A fifth category, Equity, exists only to summarize the history of all previous income and expense transactions.

Command-line accounting systems are just simplistic computer languages for conveniently entering, reading and processing this transaction data, and ensure that the constraint of the double-entry method is respected. They’re simple counting systems, that can add any kind of “thing” in dedicated counters (“accounts”). They’re basically calculators with multiple buckets. Beancount and Ledger may differ slightly in their syntax and on some of their semantics, but the general principle is the same, and the simplifying assumptions are very similar.

Here is a concrete example of what a transaction looks like, just so you can get a feeling for it. In a text file—which is the input to a command-line accounting system—something like the following is written and expresses a credit card transaction:

2014-05-23 * "CAFE MOGADOR NEW YO" "Dinner with Caroline"

Liabilities:US:BofA:CreditCard -98.32 USD

Expenses:Restaurant

This is an example transaction with two “postings,” or “legs.” The “Expenses:Restaurant” line is an account, not a category, though accounts often act like categories (there is no distinction between these two concepts). The amount on the expenses leg is left unspecified, and this is a convenience allowed by the input language. The software determines its amount automatically with the remainder of the balance which in this case will be 98.32 USD, so that -98.32 USD + 98.32 USD = 0 (remember that the sum of all postings must balance to zero—this is enforced by the language).

Most financial institutions provide some way for you to download a summary of account activity in some format or other. Much of the details of your transactions are automatically pulled in from such a downloaded file, using some custom script you write that converts it into the above syntax:

-

A transaction date is always available from the downloadable files.

-

The “

CAFE MOGADOR NEW YO” bit is the “memo,” also provided by the downloaded file, and those names are often good enough for you to figure out what the business you spent at was. Those memos are the same ugly names you would see appear on your credit card statements. This is attached to a transaction as a “payee” attribute. -

I manually added “

Dinner with Caroline” as a comment. I don’t have to do this (it’s optional), but I like to do it when I reconcile new transactions, it takes me only a minute and it helps me remember past events if I look for them. -

The importer brought in the

Liabilities:US:BofA:CreditCardposting with its amount automatically, but I’ve had to insert theExpenses:Restaurantaccount myself: I typed it in. I have shortcuts in my text editor that allow me to do that using account name completion, it takes a second and it’s incredibly easy. Furthermore, pre-selecting this account could be automated as well, by running a simple learning algorithm on the previous history contained in the same input file (we tend to go to the same places all the time).

The syntax gets a little bit more complicated, for example it allows you to represent stock purchases and sales, tracking the cost basis of your assets, and there are many other types of conveniences, like being able to define and count any kind of “thing” in an account (e.g., “vacation hours accumulated”), but this example captures the essence of what I do. I replicate all the transactions from all of the accounts that I own in this way, for the most part in an automated fashion. I spend about 1-2 hours every couple of weeks in order to update this input file, and only for the most used accounts (credit card and checking accounts). Other accounts I’ll update every couple of months, or when I need to generate some reports. Because I have a solid understanding of my finances, this is not a burden anymore… it has become fun.

What you obtain is a full history, a complete timeline of all the financial transactions from all the accounts over time, often connected together, your financial life, in a single text file.

Generating Reports

So what’s the point of manicuring this file? I have code that reads it, parses it, and that can serve various views and aggregations of it on a local web server running on my machine, or produce custom reports from this stream of data. The most useful views are undeniably the balance sheet and income statement, but there are others:

-

Balance Sheet. A balance sheet lists the final balance of all of your assets and liabilities accounts on a single page. This is a snapshot of all your accounts at a single point in time, a well-understood overview of your financial situation. This shows your net worth (very precisely, if you update all your accounts) and is also what a banker would be interested in if you were to apply for a loan. Beancount can produce my balance sheet at any point in time, but most often I’m interested in the “current” or “latest” balance sheet.

-

Income Statement. An income statement is a summary of all income and expenses that occur between two points in time. It renders the final balance for these accounts in format familiar to any accountant: income accounts on the left, expense accounts on the right. This provides insights on the changes that occurred during a time period, a delta of changes. This tells you how much you’re earning and where your money is going, in detail. The difference between the two is how much you saved. Beancount can render such a statement for any arbitrary period of time, e.g., this year, or month by month.

-

Journals. For each account (or category, if you like to think of them that way), I can render a list of all the transactions that posted changes to that account. I call this a journal (Ledger calls this a “register”). If you’re looking at your credit card account’s journal, for instance, it should match that of your bank statement. On the other hand, if you look at your “restaurants expense” account, it should show all of your restaurant outings, across all methods of payment (including cash, if you choose to enter that). You can easily fetch any detail of your financial history, like “Where was that place I had dinner with Arthur in March three years ago?” or “I want to sell that couch… how much did I pay for it again?”

-

Payables and Receivables. If you have amounts known to be received, for example, you filed your taxes or sent an invoice and are expecting a payment, or you mailed a check and you are expecting it to be cashed at some point in the future, you can track this with dedicated accounts. Transactions have syntax that allows you to link many of them together and figure out what has been paid or received.

-

Calculating taxes. If you enter your salary deposits with the detail from your pay stub, you can calculate exactly how much taxes you’ve paid, and the amounts should match exactly those that will be reported on your employer’s annual income reporting form (e.g., W2 form in the USA, T4 if in Canada, Form P60 in the UK, or otherwise if you live elsewhere). This is particularly convenient if you have to make tax installments, for instance. If you’re a contractor, you will have to track many such things, including company expensable expenses. It is also useful to count dividends that you have to report as taxable income.

-

Investing. I’m not quite rich, but I manage my own assets using discount brokers and mainly ETFs. In addition, I take advantage of a variety of tax sheltered accounts, with limited choices in assets. This is pretty common now. You could say that I’m managing a miniature hedge fund and you wouldn’t be too far from reality. Using Beancount, I can produce a detailed list of all holdings, with reports on daily market value changes, capital gains, dividends, asset type distribution (e.g. stocks vs. fixed income), currency exposure, and I can figure out how much of my assets are liquid, e.g., how much I have available towards a downpayment on a house. Precisely, and at any point in time. This is nice. I can also produce various aggregations of the holdings, i.e., value by account, by type of instrument, by currency.

-

Forecasting. The company I work for has an employee stock plan, with a vesting schedule. I can forecast my approximate expected income including the vesting shares under reasonable assumptions. I can answer the question: “At this rate, at which date do I reach a net worth of X?” Say, if X is the amount which you require for retirement.

-

Sharing Expenses. If you share expenses with others, like when you go on a trip with friends, or have a roommate, the double-entry method provides a natural and easy solution to reconciling expenses together. You can also produce reports of the various expenses incurred for clarity. No uncertainty.

-

Budgeting. I make enough money that I don’t particularly set specific goals myself, but I plan to support features to do this.

You basically end up managing your personal finances like a company would… but it’s very easy because you’re using a simple and cleverly designed computer language that makes a lot of simplifications (doing away with the concepts of “credit and debits” for example), reducing the process to its essential minimum.

Custom Scripting

The applications are endless. I have all sorts of wild ideas for generating reports for custom projects. These are useful and fun experiments, “challenges” as I call them. Some examples:

-

I once owned a condo unit and I’ve been doing double-entry bookkeeping throughout the period I owned it, through selling it. All of the corresponding accounts share the

Loft4530name in them. This means that I could potentially compute the precise internal rate of return on all of the cash flows related to it, including such petty things as replacement light bulbs expenses. To consider it as a pure investment. Just for fun. -

I can render a tree-map of my annual expenses and assets. This is a good visualization of these categories, that preserve their relative importance.

-

I could look at average expenses with a correction for the time-value of money. This would be fun, tell me how my cost of living has changed over time.

The beauty of it is that once you have the corpus of data, which is relatively easy to create if you maintain it incrementally, you can do all sorts of fun things by writing a little bit of Python code. I built Beancount to be able to do that in two ways:

-

By providing a “plugins” system that allows you to filter a parsed set of transactions. This makes it possible for you to hack the syntax of Beancount and prototype new conveniences in data entry. Plugins provided by default provide extended features just by filtering and transforming the list of parsed transactions. And it’s simple: all you have to do is implement a callback function with a particular signature and add a line to your input file.

-

By writing scripts. You can parse and obtain the contents of a ledger with very little code. In Python, this looks no more complicated than this:

import beancount.loader

…

entries, errors, options = beancount.loader.load_file('myfile.ledger')

for entry in entries:

…

Voila. You’re on your way to spitting out whatever output you want. You have access to all the libraries in the Python world, and my code is mostly functional, heavily documented and thoroughly unit-tested. You should be able to find your way easily. Moreover, if you’re uncertain about using this system, you could just use it to begin entering your data and later write a script that converts it into something else.

Filing Documents

If you have defined accounts for each of your real-world accounts, you have also created a natural method for organizing your statements and other paper documents. As we are communicating more and more by email with our accountants and institutions, it is becoming increasingly common to scan letters to PDFs and have those available as computer files. All the banks have now gone paperless, and you can download these statements if you care (I tend to do this once at the end of the year, for preservation, just in case). It’s nice to be able to organize these nicely and retrieve those documents easily.

What I do is keep a directory hierarchy mirroring the account names that I’ve defined, something that looks like this:

.../documents/

Assets/

US/

TDBank/

Checking/

2014-04-08.statement.march.pdf

2014-05-07.statement.april.pdf

…

Liabilities/

US/

Amex/

Platinum/

2014-04-17.March.pdf

2014-04-19.download.ofx

…

Expenses/

Health/

Medical/

2014-04-02.anthem.eob-physiotherapy.pdf

…

These example files would correspond to accounts with names Assets:US:TDBank:Checking, Liabilities:US:Amex:Platinum, and Expenses:Health:Medical. I keep this directory under version control. As long as a file name begins with a date, such as “2014-04-02”, Beancount is able to find the files automatically and insert directives that are rendered in its web interface as part of an account’s journal, which you can click on to view the document itself. This allows me to find all my statements in one place, and if I’m searching for a document, it has a well-defined place where I know to find it.

Moreover, the importing software I wrote is able to identify downloaded files and automatically move them into the corresponding account’s directory.

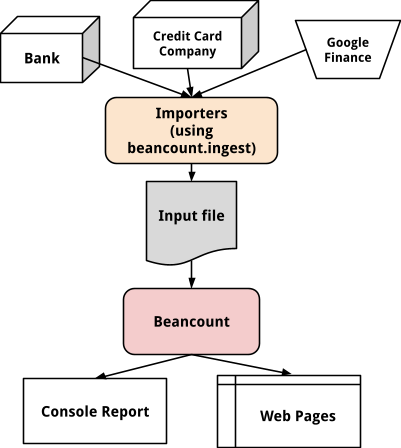

How the Pieces Fit Together

So I’ve described what I do to organize my finances. Here I’ll tell you about the various software pieces and how they fit together:

-

Beancount is the core of the system. It reads the text file I update, parses the computer language I’ve defined and produces reports from the resulting data structures. This software only reads the input file and does not communicate with other programs on purpose. It runs in isolation.

-

Beancount’s ingest package and tools help automate the updating of account data by extracting transactions from file downloads from banks and other institutions. These tools orchestrate the running of importers which you implement (this is where all the messy importing code lives, the code you need to make it easier to keep your text file up-to-date, which can parse OFX and CSV files, for instance). See bean-extract, bean-identify tools.

-

The ingest package also helps with filing documents (see bean-file tool). Because it is able to identify which document belongs to which account, it can move the downloaded file to my documents archive automatically. This saves me time.

-

Finally, in order to provide market values, a Beancount input file should have suitable price directives. Beancount also contains code to fetch latest or historical prices for the various commodities present in one’s ledger file (see the bean-price tool). Like the extraction of transactions from OFX downloads, it also spits out Beancount input syntax used to define prices.

See the diagram below for a pretty picture that illustrates how these work together.

Why not just use a spreadsheet?

This is indeed a good question, and spreadsheets are incredibly useful for sure. I certainly would not be writing my own software if I could track my finances with a spreadsheet.

The problem is that the intrinsic structure of the double-entry transactional data does not lend itself to a tabular representation. Each transaction has multiple attributes (date, narration, tags), and two or more legs, each of which has an associated amount and possibly a cost. If you put the dates on one axis and the accounts on the other, you would end up with a very sparse and very large table; that would not be very useful, and it would be incredibly difficult to edit. If on the other hand, you had a column dedicated to account names for each row, all of your computations would have to take the account cell into the calculation logic. It would be very difficult to deal with, if not impossible. All matters of data aggregations are performed relative to account names.

Moreover, dealing with the accumulation of units with a cost basis would require difficult gymnastics. I don’t even know how I would proceed forward to do this in a spreadsheet. A core part of command-line accounting systems is the inventory logic that allows you to track a cost basis for every unit held in an account and book reductions of positions against existing lots only. This allows the system to compute capital gains automatically. And this is related to the codes that enforce the constraint that all postings on a transaction balance out to zero.

I believe that the “transaction <-> postings” data representation combined with a sensible method for updating inventories is the essence of this system. The need for these is the justification to create a dedicated method to build this data, such as a computer language. Finally, having our own syntax offers the opportunity to provide other types of useful directives such as balance assertions, open/close dates, and sophisticated filtering of subsets of transactions. You just cannot do what we’re doing in a spreadsheet.

Why not just use a commercial app?

How about Mint.com?

Oftentimes people tell me they’re using Mint.com to track their finances, usually with some amount of specific complaints following close behind. Online services such as Mint provide a subset of the functionality of double-entry accounting. The main focus of these services is the reporting of expenses by category, and the maintenance of a budget. As such, they do a great job at automating the download of your credit card and bank transactions. I think that if you want a low-maintenance option to tracking your finances and you don’t have a problem with the obvious privacy risks, this is a fantastic option: it comes with a web interface, mobile apps, and updating your accounts probably requires clicking some buttons, providing some passwords, and a small amount of manual corrections every couple of weeks.

I have several reservations about using it for myself, however:

-

Passwords. I’m just not comfortable enough with any commercial company to share the passwords to all my bank, credit card, and investment accounts. This sounds like an insane idea to me, a very scary one, and I’m just not willing to put that much trust in any one company’s hands. I don’t care what they say: I worked for several software companies and I’m aware of the disconnect between promises made by salespeople, website PR, and engineering reality. I also know the power of determined computer hackers.

-

Insufficient reporting. Reporting is probably beautiful and colorful—it’s gorgeous on the website—but certainly insufficient for all the reporting I want to do on my data. Reporting that doesn’t do what they want it to is a common complaint I hear about these systems. With my system, I can always write a script and produce any kind of report I might possibly want in the future. For instance, spitting out a treemap visualization of my expenses instead of a useless pie chart. I can slice and dice my transactions in all kinds of unique ways. I can tag subsets of transactions for projects or trips and report on them. It’s more powerful than generic reporting.

-

Perennity. What if the company is not in business in 5 years? Where will my data be? If I spend any time at all curating my financial data, I want to ensure that it will be available to me forever, in an open format. In their favor, some of these sites probably have a downloadable option, but who uses it? Does it even work well? Would it include all of the transactions that they downloaded? I don’t know.

-

Not international. It probably does not work well with an international, multi-currency situation. These services target a “majority” of users, most of which have all their affairs in a single country. I live in the USA, have a past history in Canada, which involves remaining tax-sheltered investment accounts, occasional expenses during visits which justify maintaining a credit card there, and a future history which might involve some years spent in another country such as Hong Kong or Australia. Will this work in Mint? Probably not. They might support Canada, but will they support accounts in both places? How about some other country I might want to move to? I want a single integrated view of all my accounts across all countries in all currencies forever, nothing less. My system supports that very well. (I’m not aware of any double-entry system that deals with the international problem in a currency agnostic way as well as Beancount does.)

-

Inability to deal with particular situations. What if I own real estate? Will I be able to price the value of my home at a reasonable amount, so it creates an accurate balance sheet? Regularly obtaining “comparables” for my property from an eager real estate agent will tell me much more precisely how much my home is worth than services like Zillow ever could. I need to be able to input that for my balance sheet. What about those stock options from that privately held Australian company I used to work for? How do I price that? How about other intangible things, such as receivables from a personal loan I made to a friend? I doubt online services are able to provide you with the ability to enter those. If you want the whole picture with precision, you need to be able to make these adjustments.

-

Custom tracking. Using “imaginary currencies”, I’m able to track all kinds of other things than currencies and stocks. For example, by using an “

IRAUSD” commodity in Beancount I’m able to track how many 401k contributions I’ve made at any point during the year. I can count the after-tax basis of a traditional IRA account similarly. I can even count my vacation hours using an imaginary “VACHR” currency and verify it against my pay stubs. -

Capital gains reporting. I haven’t tried it myself, but I’ve heard some discontent about Mint from others about its limited capabilities for capital gains reporting. Will it maintain trade lots? Will it handle average cost booking? How about PnL on FOREX gains? What about revenue received for that book I’m selling via PayPal? I want to be able to use my accounting system as an input for my tax reporting.

-

Cash transactions. How difficult is it to enter cash transactions? Do I have to log in, or start a slow, heavy program that will only work under Windows? With Beancount I bring up a file in a text editor, this is instant and easy. Is it even possible to enter custom cash entries in online services?

In other words, I’m a very sophisticated user and yes, a bit of a control freak. I’m not lying about it. I don’t have any ideological objections about using a commercial service, it is probably not for me. If it’s good enough for you, suit yourself. Despite their beautiful and promising websites, I haven’t heard of anyone being completely satisfied with these services. I hear a fair amount of complaining, some mild satisfaction, but I have yet to meet anyone who raves about it.

How about Quicken?

Quicken is a single-entry system, that is, it replicates the transactions of a remote account locally, and allows you to add a label to each transaction to place it in a category. I believe it also has support for synchronizing investment accounts. This is not enough for me, I want to track all kinds of things, and I want to use the double-entry method, which provides an intrinsic check that I’ve entered my data correctly. Single-entry accounting is just not good enough if you’ve already crossed the bridge of understanding the double-entry method.

How about Quickbooks?

So let’s talk about sophisticated software that is good enough for a company. Why wouldn’t I use that instead? If it’s good enough for small businesses, it should be good enough for me, no? There’s Quickbooks and other ones. Why don’t I use them:

-

It costs money. Commercial software comes at a price. Ok, I probably could afford to pay a few hundred dollars per year (Quickbooks 2014 looks like around 300$/year for the full set of features), but I don’t really want to.

-

Platform. These softwares usually run on Microsoft Windows and sometimes on Mac OS X. I’m a software developer, I mostly use Linux, and a Macbook Air for a laptop, on which I get annoyed running anything other than tmux and a web browser. I’m not going to reboot just to enter a quick cash transaction.

-

Slow startup. I cannot speak specifically to Quickbooks’ implementation, but virtually every software suite of commercial scope I’ve had to use had a splash screen and a slow, slow startup that involved initializing tons of plugins. They assume you’re going to spend hours in it, which is reasonable for commercial users, but not for me, if I want to do a quick update of my ledger.

-

UIs are inadequate. I haven’t seen their UI but given the nature of transactions and my desire to input precisely and search quickly and organize things, I want to be able to edit in as text. I imagine it would be inconvenient for me. With Emacs and org-mode, I can easily i-search my way to any transaction within seconds after opening my ledger file.

- Inflexible. How would I go about re-organizing all my account names? I think I’m still learning about the double-entry bookkeeping method and I have made mistakes in the past, mistakes where I desire to revisit the way I organize my accounts in a hierarchy. With my text file, I was able to safely rename a large number of accounts several times, and evolve my chart-of-accounts to reflect my improving understanding of how to organize my financial tracking system. Text is powerful!

How about GnuCash?

I don’t like UIs; they’re inconvenient. There’s nothing quite like editing a text file if you are a programmer. Moreover, GnuCash does not deal with multiple currencies well. I find bugs in it within the first hour every time I kick the tires on it, which I do every couple of years, out of curiosity. Other programs, such as Skrooge, also take the heavy-handed big UI approach.

Why build a computer language?

A bookkeeping system provides conditions for a solution that involves a simple computer language for many reasons.

Single-entry bookkeeping is largely insufficient if you're trying to track everything holistically. Existing systems either limit themselves to expense categories with little checking beyond "reconciling" which sometimes involves freezing the past. If you're not doing the bookkeeping for a company, sometimes just changing the past and fixing the mistakes where they occurred makes more sense. More importantly, the single-entry method leaves us wanting for the natural error-checking mechanism involved in the double-entry system.

The problem is also not solvable elegantly by using spreadsheets; the simple data structure that forms the basis of the double-entry system infers either a very sparse spreadsheet with accounts on one dimension and transactions on the other. For real-world usage, this is impractical. Another iteration on this theme would involve inserting the postings with two columns, one with the account and one with the amount, but the varying number of columns and the lookup code makes this inelegant as well. Plus, it's not obvious how you would deal with a large number of currencies.

Programs that provide fancy graphical or web-based user interfaces are inevitably awkward, due to the nature of the problem: each transaction is organized by viewing it through the lens of one account's journal, but any of the accounts present in its postings provide equally valid views. Ideally, what you want, is just to look at the transaction. Organizing them for most convenient input has little to do with the order in which they are to be presented. Using text has a lot of advantages:

-

You can easily used search-and-replace and/or sed to make global changes, for example, rename or reorganize your accounts;

-

You can organize the transactions in the order that is most convenient for data entry;

-

There are a number of existing tools to search the text;

-

You can easily write various little tools to spit out the data syntax, i.e., for importing from other file types, or converting from other systems.

-

Text is inherently open, that is the file format is one that you can read your data from and store anywhere else, not a blob of incomprehensible data that becomes unusable when the company that makes the software stops supporting it.

Finally, systems that attempt to automate the process of importing all your data from automated sources (e.g., mint.com) have one major shortfall: most often it's not very easy or even possible to add information for accounts that aren't automated. It is my experience that in practice you will have some entries and accounts to track that will not have a nice downloadable file format, or that simply don't have a real-world counterpart. In order to produce a complete view of one's balance sheet, it is important to be able to enter all of an individual's account within a single system. In other words, custom accounts and manually entered transactions do matter a lot.

For all the reasons mentioned above, I feel that a computer language is more appropriate to express this data structure than a heavy piece of software with a customized interface. Being able to easily bring up a text file and quickly type in a few lines of text to add a transaction is great–it's fast and easy. The ledger file provides a naturally open way to express one's data, and can be source-controlled or shared between people as well. Multiple files can be merged together, and scripted manipulations on a source file can be used to reorganize one's data history. Furthermore, a read-only web interface that presents the various reports one expects and allows the user to explore different views on the dataset is sufficient for the purpose of viewing the data.

Advantages of Command-Line Bookkeeping

In summary, there are many advantages to using a command-line accounting system over a commercial package that provides a user-interface:

-

Fast. You don’t have to fire up a slow program with a splash screen that will take a while to initialize in order to add something to your books. Bringing up a text file from a bookmark in your favorite editing program (I use Emacs) is easy and quick. And if you’re normally using a text editor all day long, as many programmers do, you won’t even blink before the file is in front of your eyes. It’s quick and easy.

-

Portable. It will work on all platforms. Beancount is written in Python 3 with some C extensions, and as such will work on Mac, Linux and Windows platforms. I am very careful and determined to keep external dependencies on third-party packages to an absolute minimum in order to avoid installation problems. It should be easy to install and update, and work everywhere the same.

-

Openness. Your data is open, and will remain open forever. I plan on having my corpus of data until the day I die. With an open format you will never end up in a situation where your transactional data is sitting in a binary blob with an unknown format and the software goes unsupported. Furthermore, your data can be converted to other languages easily. You can easily invoke the parser I provide and write a script that spits it out in another program’s input syntax. You can place it under version control. You can entirely reorganize the structure of your accounts by renaming strings with sed. Text is empowering.

-

Customized. You can produce very customized reports, that address exactly the kinds of problems you are having. One complaint I often hear from people about other financial software is that it doesn’t quite do what they want. With command-line accounting systems you can at least write it yourself, as a small extension that uses your corpus of data.

Why not just use an SQL database?

I don’t like to reinvent the wheel. If this problem could be solved by filling up an SQL database and then making queries on it, that’s exactly what I would do. Creating a language is a large overhead, it needs to be maintained and evolved, it’s not an easy task, but as it turns out, necessary and justified to solve this problem.

The problem is due to a few reasons:

-

Filtering occurs on a two-level data structure of transactions vs. their children postings, and it is inconvenient to represent the data in a single table upon which we could then make manipulations. You cannot simply work only with postings: in order to ensure that the reports balance, you need to be selecting complete transactions. When you select transactions, the semantics is “select all the postings for which the transaction has this or that property.” One such property is “all transactions that have some posting with account X.” These semantics are not obvious to implement with a database. The nature of the data structure makes it inconvenient.

-

The wide variety of directives makes it difficult to design a single elegant table that can accommodate all of their data. Ideally we would want to define two tables for each type of directive: a table that holds all common data (date, source filename & lineno, directive type) and a table to hold the type-specific data. While this is possible, it steps away from the neat structure of a single table of data.

-

Operations on inventories—the data structure that holds the incrementally changing contents of accounts—require special treatment that would be difficult to implement in a database. Lot reductions are constrained against a running inventory of lots, each of which has a specific cost basis. Some lot reductions trigger the merging of lots (for average cost booking). This requires some custom operations on these inventory objects.

-

Aggregations (breakdowns) are hierarchical in nature. The tree-like structure of accounts allows us to perform operations on subtrees of postings. This would also not be easy to implement with tables.

Finally, input would be difficult. By defining a language, we side-step the problem of having to build a custom user interface that would allow us to create the data.

Nevertheless, I really like the idea of working with databases. A script (bean-sql) is provided to convert the contents of a Beancount file to an SQL database; it’s not super elegant to carry out computations on those tables, but it’s provided nonetheless. You should be able to play around with it, even if operations are difficult. I might even pre-compute some of the operation’s outputs to make it easier to run SQL queries.

But... I just want to do X?

Some may infer that what we’re doing must be terribly complicated given that they envision they might want to use such a system only for a single purpose. But the fact is, how many accounts you decide to track is a personal choice. You can choose to track as little as you want in as little detail as you deem sufficient. For example, if all that you’re interested in is investing, then you can keep books on only your investment accounts. If you’re interested in replacing your usage of Mint.com or Quicken, you can simply just replicate the statements for your credit cards and see your corresponding expenses.

The simplicity of having to just replicate the transactions in all your accounts over doing a painful annual “starting from scratch” evaluation of all your assets and expenses for the purpose of looking at your finances will convince you. Looking at your finances with a spreadsheet will require you to at least copy values from your portfolio. Every time you want to generate the report you’ll have to update the values… with my method, you just update each account’s full activity, and you can obtain the complete list holdings as a by-product. It’s easy to bring everything up-to-date if you have a systematic method.

To those I say: try it out, accounting just for the bits that you’re interested in. Once you’ll have a taste of how the double-entry method works and have learned a little bit about the language syntax, you will want to get a fuller picture. You will get sucked in.

Why am I so Excited?

Okay, so I’ve become an accounting nerd. I did not ask for it. Just kind-of happened while I wasn’t looking (I still don’t wear brown socks though). Why is it I can’t stop talking about this stuff?

I used to have a company. It was an umbrella for doing contract work (yes, I originally had bigger aspirations for it, but it ended up being just that. Bleh.) As a company owner in Canada, I had to periodically make five different kinds of tax installments to the Federal and Provincial governments, some every month, some every three months, and then it varied. An accountant was feeding me the “magic numbers” to put in the forms, numbers which I was copying like a monkey, without fully understanding how they were going to get used later on. I had to count separately the various expenses I would incur in relation to my work (for deductions), and those which were only personal —I did not have the enlightened view of getting separate credit cards so I was trying to track personal vs. company expenses from the same accounts. I also had to track transfers between company and personal accounts that would later on get reported as dividends or salary income. I often had multiple pending invoices that would take more than two months to get paid, from different clients. It was a demi-hell. You get the idea. I used to try to track all these things manually, using systems composed of little text files and spreadsheets and doing things very carefully and in a particular way.

The thing is, although I am by nature quite methodical, I would sometimes, just sometimes forget to update one of the files. Things would fall out of sync. When this happened it was incredibly frustrating, I had to spend time digging around various statements and figure out where I had gone wrong. This was time-consuming and unpleasant. And of course, when something you have to do is unpleasant, you tend not to do it so well. I did not have a solid idea of the current state of affairs of my company during the year, I just worked and earned money for it. My accountant would draw a balance sheet once a year after doing taxes in July, and it was always a tiny bit of a surprise. I felt permanently somewhat confused, and frankly annoyed every time I had to deal with “money things.” It wasn’t quite a nightmare, but it was definitely making me tired. I felt my life was so much simpler when I just had a job.

But one day… one day… I saw the light: I discovered the double-entry method. I don’t recall exactly how. I think it was on a website, yes… this site: dwmbeancounter.com (it’s a wonderful site). I realized that using a single system, I could account for all of these problems at the same time, and in a way that would impose an inherent error-checking mechanism. I was blown away! I think I printed the whole thing on paper at the time and worked my way through every tutorial. This simple counting trick is exactly what I was in dire need for.

But all the software I tried was either disappointing, broken, or too complicated. So I read up on Ledger. And I got in touch with its author. And then shortly after I started on Beancount1. I’ll admit that going through the effort of designing my own system just to solve my accounting problems is a bit overkill, but I’ve been known to be a little more than extreme about certain things, and I’ve really enjoyed solving this problem. My life is fulfilled when I maintain a good balance of “learning” and “doing,” and this falls squarely in the “doing” domain.

Ever since, I feel so excited about anything related to personal finance. Probably because it makes me so happy to have such a level of awareness about what’s going on with mine. I even sometimes find myself loving spending money in a new way, just from knowing that I’ll have to figure out how to account for it later. I feel so elated by the ability to solve these financial puzzles that I have had bouts of engaging complete weekends in building this software. They are small challenges with a truly practical application and a tangible consequence. Instant gratification. I get a feeling of empowerment. And I wish the same for you.

-

For a full list of differences, refer to this document. ↩